Artillery Destroys Everything.

Just look at the trends. The proportion of casualties that artillery inflicts has been growing since the First World War. Artillery preceding the middle of the nineteenth century did have an equal share of the bounty with other means of destruction, and there was a significant increase in the stock of small arms in those intervening years, relegating The God Of War to mortal status with only a 10% share, but a fundamentally different ratio was born in 1914.

The Second World War saw various theatre figures of 45-70%, but major conventional conflicts since find a steady bracket of 60-85%, depending on your favourite number-collecting historian.

Maj Gen Bailey provides most of these figures but the recent trends are ones that are well recognised.1 Each contemporary conflict has appeared to reinforce the matter. A curious draft paper from the opening exchanges of the Russo-Ukraine War further cemented this meme among staff officers, with the regular quoting of an 80% casualty share for St Barbara’s own.2

Let us consider some tangible examples of this phenomena.

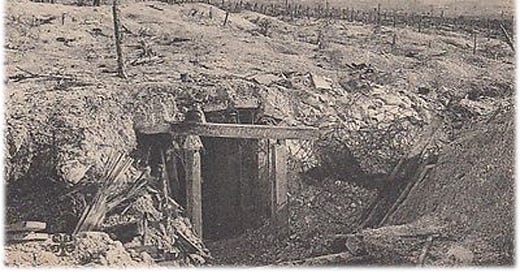

This is the Mont Cornillet Tunnel. In 1917, a strike on the entrance of this tunnel resulted in 400 Germans trapped and buried alive. Decisive and destructive results from our trusted arm. Artillery destroys everything.

This is ‘Zelenopillia’, early July 2014. And what happened here? What destruction did our professional body wreck?

These images show the aftermath of a Russian strike upon an assembly of elements from several Ukrainian military and police brigades. With over a hundred casualties and the loss of two battalions worth of vehicles, the devastation wrought is a clear demonstration that artillery destroys everything. For the Western peacetime staff officers of 2014, this was the starkest image of what conflict will be like with an increasingly likely, but still vague, adversary like Russia: you will be found and you will be killed.

This enhanced image captures a failed Russian crossing during the Battle of the Siverskyi Donets. This attempt made in early May 2022 was one of several, with this particular engagement reportedly destroying an entire battalion tactical group. The head of the Luhansk Regional Military Administration reported the defeat of almost 100 units of equipment and almost a 1,000 soldiers. Artillery destroys everything.

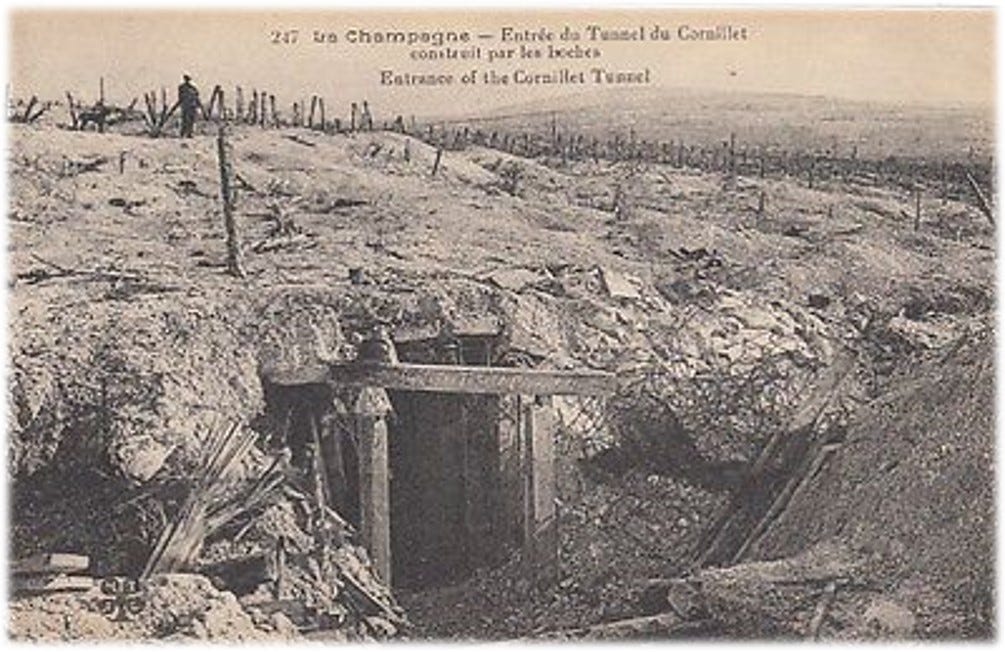

During the Battle of Verdun, on 22 June 1916, German batteries (26 heavy and 9 light) fired 100,000 high explosive and gas shells on the village of Fleury.3 Such was the destruction, that the village was essentially removed from the landscape.

Say it with me now: artillery destroys everything.

The natural consequences of this popular meme of destruction is a focus on battle of the deep kind. That is, on the means of destroying the opposing army before it makes proper contact with ones own, regardless of who is doing the advancing. We must fight the ‘deep battle’, thus ensuring an ‘anti-climatic close’. After all, if the majority of the enemy casualties succumb to fire from our defilade positions, then do we even need anyone else to show up?

Let us consider some other scenes.

This may well look the same, but it is a remarkably different situation from the one previously described. If we were to pay a visit to the village-formerly-known-as Fleury in June 1916, we would find a large number of French machine guns taking cover in the cellars and rubble. These men survived and continued the fight. The Germans had to clear these positions one by one with hand grenades and flamethrowers. Fleury was literally pulverised, but still, there was no anti-climatic close.

A single machine gun can hold a much greater force, as a few German editions demonstrated on a number of occasions during the Second World War. Training staff at the British Army Training Unit Suffield (what was the collective training centre for British armoured forces) could witness on any exercise season examples of a single anti-tank post pausing an advancing tank troop in its tracks. Where a troop stops, a squadron halts, and so the battle group hesitates, and the brigade considers an interlude.

All it takes for an objective to offer decisive resistance turns out to be merely a few determined men in the right place. And this is a story that we could repeat in any war: artillery destroys nothing.

And what of the Mont Cornillet Tunnel? Well this indeed was a tragedy. The only thing worse than being buried alive, is not being able to commit your reserve, and here the Germans suffered both.

This is the effect of the ‘lucky shot’. There probably wasn’t an intention to hit that specific tunnel with the shell and gun that did, although there almost certainly was an intention to prevent the deployment of reserves.

Mont Cornillet Tunnel rhymes a little with Fleury in the sense that: if you fire enough, it will be destroyed. This sentiment is true. There is something to the fire destruction tables, ‘whizz wheels’ and nomograms that abound. However, these handy guides whisper to artillery staff officers a type of false certainty: that quantity of fire might well destroy 30% of the opposition, but you don’t know which ones.

And that is before we even get into the quantities required. If any other arm was expending such extraordinary energy for such a small proportion of it to have any effect, we would regard that arm as remarkably inefficient, and perhaps use it as evidence for not bothering. When the whole orchestra is considered against the ratio of useful outcomes, we might start to think that artillery destroys nothing.

A pair of other angles on the fire strike of ‘Zelenopillia’.

What do we see now? Trucks. Beds. Pull up bars.

This is a mounting area that had been occupied for some time, 9km from the Russian border, and with reports of overflights of drones. A total of 36 dead and a significant number of vehicles. Much destruction was wrought, but not quite the initial numbers that circulated among fearful Western staff officers, and the former images were selected over the later.

It took some years before the narrative gained some balance, which raises the question about how different interpretations of events are framed. Who is it that wants this scene to be depicted as absolute and menacing destruction? Russia does; the spread of a mythos of a ruthless army possessing a terrifying competence with artillery is probably useful. But it is also handy, in the opening scenes of that conflict, for Ukraine to characterise Russian forces as the same, thus giving the greatest opportunity to justify the events and to use them to invite the support of others.4

A more holistic picture built later on tells us a story of some complacency, but also some lessons.

Considering the Battle of the Siverskyi Donets, the problem here is not the loss of a ‘battalion tactical group’. It is the failure to cross. Perhaps the only thing worse than not being able to commit your reserve, is to not be able to cross the river.

If other sites had been successful, or this was the price to put enough force on the other side with sufficient momentum, then this image might be well be a bargain. If the next significant events of the war were a victory parade in Kyiv, then these images would become icons of the price of success rather than a testament to wasteful suffering.

Equally, because of that loss, this is unlikely to be repeated. Tactics is an interplay, where both forces are educating each other all the time. Here, the Ukrainians didn’t just destroy a concentrated crossing group, they also taught the Russians not to provide such targets again. Just as ‘Zelenopillia’ provides the thinking material, and therefore catalyst for change, to the Ukrainians.

Given time, and the proper education, artillery destroys nothing.

Artillery, the high explosive, area-treating sort, does export much destruction, maybe even, as the statisticians tell us, most of it. However, the telos of such artillery is really less about destroying, and much more about a curious combination of mischief and neighbourliness. Follow me on this trajectory, and we will explore some other fascinating features of St Barbara’s Arm in subsequent posts.

Field Artillery and Firepower (2004) by Maj Gen JBA Bailey, p5. Readers are invited to share any contradictory reports.

“Lessons Learned” from the Russo-Ukrainian War (draft 8 July 2015) by Dr Phillip A Karber.

If I recall correctly, either in Bruce Gudmundsson’s On Artillery or On Infantry (books unfortunately not to hand). From Bruce Gudmundsson, the author of the referenced works: “I tell the tale of the German attack on Fleury in both 'Storm Troop Tactics' and 'On Artillery'. Of the two accounts, the one in 'Storm Troop Tactics' goes into greater depth.”

That is not to pass comment on the rightness, militarily or politically, but merely to observe the incentives.

I spent four years in the infantry and seventeen in artillery and I never heard anyone say “artillery destroys everything.” In fact, the doctrinal definition of “destroy” is causing 30% casualties (KIA and WIA) on a particular target.

Thank you, Sir, for mentioning my books.

I tell the tale of the German attack on Fleury in both 'Storm Troop Tactics' and 'On Artillery'. Of the two accounts, the one in 'Storm Troop Tactics' goes into greater depth.