The Imperial War Museum has the most fantastic collection of videos for educating Gunners of the observing kind.

They are worth watching in full:

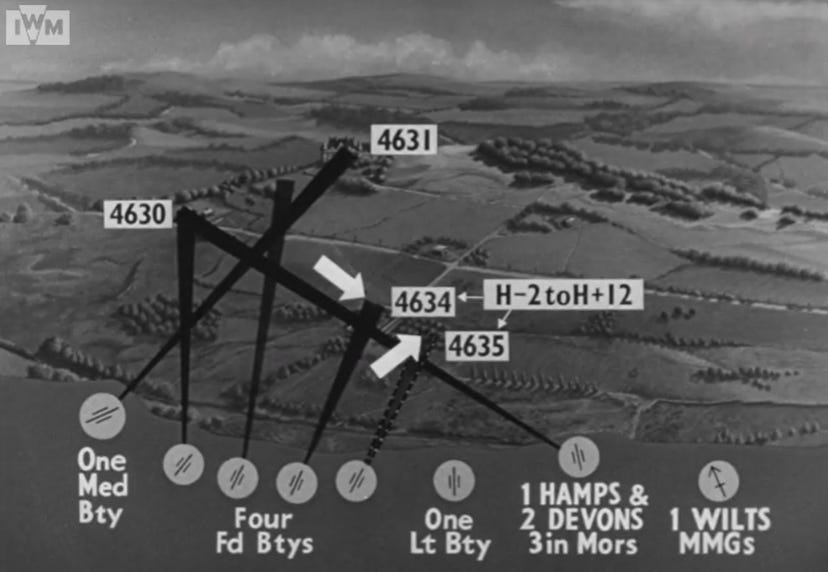

The Quick Fire Plan - a hasty plan for fires made by a Forward Observation Officer ‘in contact’.

The Deliberate Fire Plan. A fire plan with a generous helping of that rare ingredient: time.

The Making of a Fire Plan. An instructor takes his students on a journey, studying the process, and variety, within fire planning.

This gentleman is a commander of a Company. He is an ‘infanteer’ and is therefore mostly concerned about, to use contemporary parlance, ‘closing with and killing the enemy’. He is a man interested in assaulting objectives. He has sympathy for fire support, having wielded an assortment of weapons himself. Most of these are carried about the person, but some are a team sport, with a small portion of those firing indirectly.

This gentleman is a Forward Observation Officer. A senior one. He not only orders the fire of gun batteries, he also coordinates the activity of subordinate observers. Through his gentle prompts, teams of gunners will project high explosive from defilade positions.

He has a different perspective from the manoeuvre arm commander. Not just on the matter at hand, but on almost any tactical matter that both parties scrutinise. He sees targets more readily than objectives. He still sees positions to be assaulted, since he is entirely preoccupied with fire support, and rendering it to the other gentleman. But when an objective is pointed to, he would need to move quite far along in his thinking before he starts considering, for example, which objectives necessarily need to be assaulted and which may result in soldiers getting ‘stuck’ - which would be some of the initial thoughts of the infanteer.

The FOOs first thoughts, on the other hand, will be to the angle of the fire, the quantity and coordination of the treatment administered, and time (of which he is much more a servant than a master of). His next thoughts will be about composing a harmony with his bandmate - chewing on the compromises that present themselves, and determining what clusters of solutions best attend to their collective interests, in pursuit of the same higher aims.

Note in the films how the perspectives are interwoven. There is exploration and suggestion, contrarian points are entertained. There is a problem space that they are moving within and shaping - a space that exists between them. There are no fixed goals, as they too will change as the problem is explored, and will certainly change when their plan starts nudging against an enfilading reality.

This is The Joy of Arms - each bringing their own perspectives to the melting pot of the task at hand, the tasks to come, and entirely different tasks that none imagined but nevertheless barge their way into the middle of the interested parties.

It is entirely possible, and indeed best, to do as much of this wrestling in advance as circumstances allow. Better still to do it over a meal, and some drinks, frequently.

“If you want to have a productive conversation, you have to set the table.”1

Persons of a naval persuasion are accustomed to this. Floating fleets of steel yield few opportunities to meet face to face, and this author presumes that adds additional pressure to exploit the building of mutual understanding in advance - whether Nelson conveying his own meditations and predictions to his commanders, or a naval task group considering how to resolve some misunderstandings over the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands.

Now we could put all of these characters together in the first place. We can gain some things by putting them in the same Regiment. For one, breaking bread would be routine. These gentlemen would know each other, and they would probably cooperate better. They could become something more like the department culture that permeates the other services; becoming focused on trades rather than Arms.

But then something is lost. The most significant loss would be the bringing together of two or more distinct perspectives. Their cooperation would become different.

These gentlemen went to war together in Mesopotamia in the early 1990s, and, in fulfilling roles similar to those depicted in the Imperial War Museum instructional films, faced ‘problems that rhyme.’

Just like the protagonists in the films, Andrew and Mike were probably well aligned in higher aims, but they also faced plenty of opportunity for misalignment - that is, conflict of the internal kind in respect to aims and method.

Fortunately, Andrew and Mike were neighbours, and thus had the opportunity to establish a relationship to transcend such critical, but potentially adversarial, matters.

“Adversaries can both be ‘good’ to and for one another because of their very opposition, which enables each to be more itself, and additionally allows something quite new to arise from their conjunction.”2

Opposites, adjacents, near and distant cousins, all need one another. Their cooperation makes each more than it otherwise would be. Not just in that ‘whole’ and ‘sums of parts’ way, but in a way that they cannot fully realise themselves without that thing that lives between them.

You can read about Andrews perspective of events here, thus giving you access to, perhaps, half of that essential thing of cooperation: the relationship.

The Matter With Things Vol 1, by Iain McGilchrist - page 392.